Fernando Chelle

jueves, 25 de enero de 2018

Teatro Adolfo Mejía (Cartagena de Indias)

A continuación, les dejo un video con lo que fue mi intervención, con la lectura de poemas, en el Teatro Adolfo Mejía, de Cartagena de Indias, en el XV Parlamento Internacional de Escritores, la noche del 23 de agosto de 2017.

LAS MIL Y UNA PÁGINAS & LOS ELEGIDOS DEL PARNASO

A continuación, les dejo el enlace al programa “Diáspora”, del jueves 25 de enero de 2018, donde en las dos secciones, "Las mil y una páginas" y "Los elegidos del parnaso" se homenajea, con la lectura de poemas, a Nicanor Parra.

Fernando Chelle

PALABRA ESCRITA 36

A continuación, les dejo el enlace al programa número 36 de “Diáspora” (jueves 18 de enero de 2017). Tema central, análisis literario de la "Rima XV", de Gustavo Adolfo Bécquer.

Fernando Chelle

miércoles, 24 de enero de 2018

LAS MIL Y UNA PÁGINAS & LOS ELEGIDOS DEL PARNASO

A continuación, les dejo el enlace al programa “Diáspora”, del jueves 28 de diciembre de 2017. En la sesión "Las mil y una páginas" encontrarán la lectura de dos textos pertenecientes al libro "Motivos de Proteo" del escritor uruguayo José Enrique Rodó y en "Los elegidos del parnaso" la lectura de tres poemas del escritor del Renacimiento español, Fray Luis de León.

Fernando Chelle

martes, 16 de enero de 2018

Book: The Latin American short-story in the 20th Century

The Latin American short-story in the 20th Century

Fernando Chelle

Translation by Jesús Daniel Ovallos

- Editorial: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform; 1st edition (January 8, 2018)

- ISBN-10: 1983680001

- ISBN-13: 978-1983680007

Paper edition (US $): here

Kindle Edition (US $): here

Paper edition (EUR): here

Kindle Edition (EUR): here

Prologue by the author

The diversity of the Latin American short stories

In the month of June in 2015, after publishing El cuento fantástico en el Río de laPlata (The fantastic short-story in Río de la Plata), I committed myself to keep working on literary essays, about short-story writers who had ventured into the fantasy genre, but this time, not only in the region of Río de la Plata; I was interested in extending those examinations in order to study different authors, starting with the Latin American ones. About the writers from my country, I had already worked on El almohadón de plumas (The feather pillow) by Horacio Quiroga, a short story about the unexplainable death of a woman after being attacked by a strange animal that lives in a pillow; I also had published two studies about Felisberto Hernández: one about the upholders and the detractors of his works, and another which approaches a literary analysis of the short storyMuebles: el canario (The canary: Furniture shop), a wonderful narration in which, in a very fantastic way, makes a ruthless critic to the media in service to the commercial advertising. I also had already worked on some writers who had approached the fantastic genre in Argentina. I had published a study about “El Aleph”, by Jorge Luis Borges, a story which main topic is the clash between one single person and the infinite, represented in an object; and, at last, with occasion of the Julio Cortazar’s one hundredth’s birthday, I published a study about La continuidad de los parques (Continuity of the parks), his terrific story in which the writer moves around the different levels of fiction with incommensurable mastery. One of the fantastic short stories I have always liked, which has had a great impact on me since the first time I read it was El guardagujas (The switchman), by Mexican writer Juan José Arreola, so I continued my essay journey about LatinAmerican short-story writers with that text. The switchman is a story that allows a multiplicity of interpretations, some more evident than others, but there we can appreciate a satire about the Mexican railroad system; a critic to dehumanizing mercantilism; an allegory about the fate of mankind; an absurd look to some political systems and social institutions; a great work indeed. After working in the story of Arreola, I decided to change my primary plans, I would no longer continue to look for stories with fantastic characteristics throughout the American continent, but I would choose the stories that I considered the best or more representative of each country. I realized that I would have chosen the foretold stories and put them in a selection of the best Latin American short stories of the past century. If I reduced my search specter only to those stories which held fantastic characteristics, I would be taking the risk of choosing stories of a minor quality because, as I expressed in the prologue of The fantastic short story in the Río de la Plata, that characteristic was more intense in the Río de la Plata than in the rest of Latin America. Thus, I decided to change the main project, which was writing a big essay about the fantastic short stories in Latin America (a job very unlikely to be finished, if you ask me), to a more ambitious and subjective one, writing a work about the best short stories and short story writers in Latin America in the 20thcentury.

Now that the work is complete, I see that it can be divided into four thematic blocks, something that wasn’t initially planned. We have the block concerning the aforementioned five stories. A second block consisting in short stories about the teenager world. These tales are: Clandestine happiness by Clarice Lispector, a story about evil, moral suffering and the humiliation of a young girl in the hands of a girl from her same school; Día domingo (On Sunday) by Mario Vargas Llosa, a short story about the clash between two young boys for the love of a girl; in the end, we’ll approach Un regalo para Julia (A gift for Julia) by Francisco Massiani, which shares the teenager thematic with the other stories, but focuses in the insecurities and uncertainties of the aforementioned period of the life. The third block consists in only two short stories which axis is the Guerra del Chaco (Chaco War), a war that faced Bolivians and Paraguayans between 1932 and 1935. One of this tales is La excavación (The excavation) by Augusto Roa Bastos, a tale that narrates the agonic struggle of a man trying to achieve his freedom, in which he references both the internal Paraguayan wars and the mentioned Chaco War. The other short story in this block approaches the other side of the war, from the Bolivian side. I am talking about a story named El pozo (The well), a short story about the despair and hope of a group of bolivian soldiers who protect a barren well in which they try to get water from, uselessly, but for which they are willing to give their lives if necessary, in a totally useless war, like the Chaco War itself. Finally, in the fourth and last block of studied short stories, we will take a look into the works of three authors with an own characteristic voice that makes them different from the rest of the other writers. Here we will see Sensini, probably the most recognized and representative story by Roberto Bolaño about literary creation and literary contests. It is a text which unveils the struggling reality that exiled non consecrated writers have to coup in the small towns’ literary contests, which is not glory and recognizement, but just an economical relief that allows them to ease their daily needs. Another author with an own voice, that we can appreciate in this block of arbitrary classifying I decided to establish, is Gabriel García Márquez. From the Colombian author, I chose to analyze a tale titled Un día de estos (One of these days), included in his first short stories book Los funerales de la Mamá Grande (Big Mama’s funeral). It is a tale that shows a truce established in the ideological conflict between the people (represented by a dentist) and the Government (represented by a Mayor) and the reversion of roles in which the people, at least for a short moment, impose their rules. The last text in this block isUn hombre muerto a puntapiés (A man dead by kicks), written by the best Ecuadorian short story writer ever, Pablo Palacio. It is a story in which the main topic is the aggression, the violent behavior and the social problems deriving from the reluctance to accept different sexual preferences in the city of Quito by the times in which the author lived.

Fernando Chelle

Book: The fantastic short story in Río de la Plata

The fantastic short story in Río de la Plata

Fernando Chelle

Translation by Jesús Daniel Ovallos

- Editorial: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform; 1st edition (January 10, 2018)

- ISBN-10: 1983757489

- ISBN-13: 978-1983757488

Paper edition (US $): here

Kindle Edition (US $): here

Paper edition (EUR): here

Kindle Edition (EUR): here

Prologue by the author

The fantastic storytelling mania

Among the different literary manifestations that have proliferated in both strands of Río de la Plata, the fantastic short story has been one of the most outstanding. Uruguay and Argentina have been the birthplace of many excellent novelists, poets and playwrights whose names will live forever in the history of Latin American and world literature, but the most studied and most relevant authors of this region have been those who devoted their words to short stories, and within them, those who dabbled in the fantastic genre.

It is not easy to establish a reason why this kind of literature was more intense in the Río de la Plata than in the rest of Latin America, perhaps there is no definitive explanation to clarify this fact. Julio Cortázar said once that, possibly, this proliferation was due to the fact that the surrounding reality of the countries of the Río de la Plata is much poorer than the rich tropical environment surroundings of the countries that are located in the northern side of the continent. It is a possibility to which we must add at least another reason, more relevant in my opinion: the literary influences that the authors of the early and mid-20th century from Río de la Plata had. Among the most notorious influences, some of them openly recognized by different authors from that region, we can highlight the North Americans Edgar Allan Poe and Henry James (though James, almost in the end of his life, got the British nationality); we can also highlight the influence of German writer Theodor Amadeus Hoffman; Czech Republic’s Franz Kafka; France’s Jules Verne; Ireland’s Charles Maturin; Great Britain’s Thomas de Quincey, Ann Radcliffe, Mary Shelley, Herbert George Wells and Keith Chesterton, among many other influential but less noted authors.

The fantastic vein within literature is as ancient as literature itself. If we wanted to establish the origin and development of this literary line, we would have to go back to classical myths, go through some medieval literary manifestations, then follow the path of chivalric novels, and also take a look at some romantic and gothic stories. But if we wanted to theorize about that literary line, which has been present in all periods of time and has been present in many diverse literary manifestations, we would have to find out what they have in common; how, for example, a classic myth and a gothic novel are related, or how those manifestations are related to a story by Leopoldo Lugones. The answer to this question would be: the disturbing strangeness. The works in the Fantastic genre try to show a different reality than the historically recognizable reality. The facts and phenomena considered fantastic literature oppose to the natural laws, they do not imitate the reality, but they create other alternative realities that overcome or surpass what is credible or recognized as real. Of course, these supernatural elements are way different in a mythological story than in a modern civilization’s story, where the explanation of that "other reality" does not have an answer linked to divinities, but to rationality and science, as long as it can be explained by them. This has led some theorists to delimitate the fantastic, to establish a more precise definition of a term that, as I mentioned before, has been used to put works with different styles and characteristics in the same bag. As the intention of this book is not to theorize about the concept of the fantastic, but to show a series of analytical comments of some stories with similar characteristics written by authors from the Río de la Plata zone, I will present a brief description of its characteristics, and then I will just refer some concepts mentioned by Tzvetan Todorov in his 1980’s The Fantastic: A Structural Approach to a Literary Genre, so the non-experienced reader can have an idea of the concept.

The fantastic short stories in Río de la Plata in the 20th century are characterized for being brief narrations that have supernatural elements in believable environments. We can see this particular characteristic (with some differences between each story) in every story studied in this book. All of them have an average character that lives normal, daily life situations, but somehow suffer strange phenomena that cannot be explained from a realistic point of view. These stories cause an impression to the reader who, ultimately, ends up being an accomplice to this fiction, and ends up accepting the facts shown in the story as true.

In the aforementioned book, Tzvetan Todorov characterized and classified the stories with fantastic features in three categories:

First, he refers to “the marvelous”, which is when something supernatural is explained by establishing new rules for the nature. Later he refers to “the uncanny”, which happens when the supernatural event is explained through rationality. The uncanny, the author explains, happens when something familiar to us becomes something unknown, but in the end of the uncanny stories, the rupture of reality is explained. Finally “the fantastic” is linked by Todorov with a rupture in the daily life matrix. Normality is broken because there is an extraordinary event, a conflict between believable happenings and others considered unreal. At the end of the fantastic story, we do not know exactly what is going on or if the conflict is solved. and we end up perceiving the phenomenon as unexplainable.

While reading the commentaries on this book, the reader will be able to notice some of the characteristics and typical topics of the fantastic literature from Río de la Plata in the twentieth century.

One of the most characteristic features of the fantastic storytellers, even though this is not seen in all of the stories, is the use of a first person narrator; this is a resource that tries to make the reader believe something that otherwise would be unconceivable. This kind of narrator can be seen in two of the short stories I approach in this book: The Canary, furniture shop by Felisberto Hernández andThe Aleph, by Jorge Luis Borges.

As for the topics, they are so many and so diverse that I will refer only to those which are present in the stories worked on in this book.

First, the treatment of the mental deviations and the psychological problems is a recurrent topic in many of Horacio Quiroga’s short stories (The feather pillow, the lone man, The decapitated chicken, among others), but it is also typical in Felisberto Hernández works: he even studied some pathologies of mental patients. Love is not a recurrent topic in fantastic literature, but coincidentally, two of the stories approached in this book revolves around it; but in them, love is always linked to the impossible, the difficulty, (this can be seen in The feather pillow by Horacio Quiroga and in Continuity of the parks by Julio Cortázar). In fantastic literature, independently of the topic approached, it is frequent to see the writers playing with the concepts of time and space inside their narration, and it can be clearly seen in Continuity of the parks by Julio Cortázar and in The Aleph by Jorge Luis Borges.

This book consists in five articles that have been previously released on three magazines: Revista Digital VADENUEVO (Uruguay), Realidades y Ficciones – literary magazine – (Argentina) and Revista Cronopio (Colombia). There are many representatives of the fantastic short story in Río de la Plata. I could have worked on stories by Macedonio Fernández, Leopoldo Lugones, Silvina Ocampo, Enrique Anderson Imbert, Adolfo Bioy Casares, MaRío Arregui, among others, but I decided to choose those which, in my opinion, are the most representative ones: Horacio Quiroga (Uruguay), Felisberto Hernández (Uruguay), Jorge Luis Borges (Argentina) and Julio Cortázar (Argentina).

Fernando Chelle

jueves, 11 de enero de 2018

CONCURSO LITERARIO "MARINA CAPRIZ" 2017

Tercer premio CONCURSO LITERARIO "MARINA CAPRIZ" 2017 (categoría cuento), organizado por la Biblioteca Popular Rafael Obligado de Villa Gesell, Buenos Aires, Argentina (diciembre de 2017).

Resultados del premio en la página oficial de Facebook de la Biblioteca Popular Rafael Obligado de Villa Gesell:

Fernando Chelle

VIII PREMIO INTERNACIONAL DE POESÍA CAÑOS DORADOS

Ganador del VIII PREMIO INTERNACIONAL DE POESÍA CAÑOS DORADOS, organizado por el Ayuntamiento de la Villa de Fernán Núñez y la Asociación Cultural Los Caños Dorados, de la ciudad de Córdoba, España (agosto de 2017)

Resultados del concurso, en la página oficial de la Asociación Cultural Los Caños Dorados:

Fernando Chelle

PREMIO REGIONAL DE PERIODISMO

Ganador del PREMIO REGIONAL DE PERIODISMO, organizado por el Círculo de Periodistas y Comunicadores de Norte de Santander, Colombia (agosto, 2017).

Información sobre la obtención de este premio en la página oficial de la Universidad Francisco de Paula Santander:

Referencia al premio en la página del Círculo de Periodistas de Bogotá:

Fernando Chelle

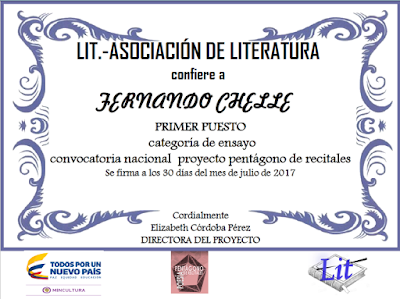

PREMIO NACIONAL DE ENSAYO LITERARIO

Ganador del PREMIO NACIONAL DE ENSAYO LITERARIO, organizado por Lit. Asociación de literatura, Colombia (julio, 2017).

Publicación del resultado por parte de Lit. Asociación de literatura, en su página oficial de Facebook:

Fernando Chelle

V CONCURSO LITERARIO DE POESÍA Y NARRATIVA

Primera mención en narrativa, V CONCURSO LITERARIO DE POESÍA Y NARRATIVA, organizado por el ESPACIO MIXTURA, de la ciudad de Montevideo, Uruguay (agosto, 2016).

ESPACIO MIXTURA

Fernando Chelle

III CONCURSO INTERNACIONAL DE POESÍA “LA PALABRA DE MI VOZ”

Primera mención en poesía, III CONCURSO INTERNACIONAL DE POESÍA “LA PALABRA DE MI VOZ”, organizado por la editorial: Publicaciones Entre Líneas, de la ciudad de Miami, EE. UU (agosto, 2016).

Ganadores del concurso. Página oficial de la editorial:

Fernando Chelle

XI CONCURSO LITERARIO BONAVENTURIANO DE POESIA y CUENTO 2016

Mención en poesía, XI CONCURSO LITERARIO BONAVENTURIANO DE POESIA y CUENTO 2016, organizado por la Universidad de San Buenaventura, de la ciudad de Cali, Colombia.

Concurso

Bonaventuriano de

Cuento y Poesía

Premios y menciones

de la duodécima edición 2016

Universidad de San Buenaventura

Cali

Dirección de Bienestar Institucional

Área Artística y Cultural

Concurso bonaventuriano de cuento y poesía

Año 12, No.12 - Septiembre de 2016 - Publicación anual

© Universidad de San Buenaventura Cali

Editorial Bonaventuriana

ISSN: 2248 - 6690

Fernando Chelle

martes, 2 de enero de 2018

RIMA XV, DE GUSTAVO ADOLFO BÉCQUER

Una incesante y romántica lucha por obtener lo

inalcanzable

Por Fernando Chelle

El presente texto es una continuación del trabajo

comenzado hace unos meses, sobre las Rimas de Gustavo Adolfo

Bécquer. Luego de un estudio general, introductorio, de las características de

la lírica becqueriana, me detuve en la Rima

I, luego en la VII y hoy es el

turno de la XV.

XV

rizada

cinta de blanca espuma,

rumor

sonoro

de

arpa de oro,

beso

del aura, onda de luz:

eso

eres tú.

voy a

tocarte te desvaneces

¡como

la llama, como el sonido,

como

la niebla, como el gemido

del

lago azul!

en el

vacío cometa errante,

largo

lamento

del

ronco viento,

ansia

perpetua de algo mejor,

¡eso

soy yo!

los ojos vuelvo de noche y día;

yo, que incansable corro y demente

¡tras una sombra, tras la hija ardiente

de una visión!

Si

quisiéramos hacer una estructura interna del libro de las Rimas de Gustavo Adolfo Bécquer, lo podríamos dividir en cuatro

partes bien diferenciadas por las temáticas tratadas. La primera parte estaría

comprendida por las rimas I a IX, que es donde el poeta sevillano se

centra en el tema de la poesía misma, de la relación del poeta con el lenguaje,

del hacer poético. De esta primera parte son los dos textos que he estudiado

hasta el momento, la Rima I y la VII, poemas que, como hemos visto,

reflexionan sobre el hecho poético. La segunda parte, que es donde se encuentra

el poema con el que voy a trabajar en el presente estudio, contiene las rimas

vinculadas con el tema amoroso, esta parte iría de la Rima X a la XXIX. En la

tercera parte, que abarcaría las rimas que van de la XXX a la LIV, también se aborda

el tema amoroso, pero aquí se encuentran las rimas que están más bien

vinculadas al desencanto, a la pérdida del amor. Es como si el tema del amor

apareciera luminoso en la segunda parte y comenzara a oscurecerse en la

tercera, para dejar el camino allanado para que el poeta se centre en el tema

de la soledad y la angustia, que es lo que vemos en el cuarto y último momento,

en las rimas que van desde la LV a la

LXXXIV.

Este

poema presenta una estructura externa muy particular. Es una composición de

cuatro estrofas, la primera presenta la misma métrica que la tercera y la

segunda la misma que la cuarta. Las estrofas uno y tres son de seis versos,

tres de ellos decasílabos (primero, segundo y quinto) y los otros tres

pentasílabos (tercero, cuarto y sexto), los dos últimos versos de cada estrofa

son agudos, esto ayuda a la musicalidad. En estas estrofas riman entre sí en

consonante el primer verso con el segundo y el tercero con el cuarto y en

asonante el verso quinto con el sexto. Las estrofas dos y cuatro son de cinco

versos, los cuatro primeros decasílabos y el quinto pentasílabo y también

agudo. Los cuatro primeros versos de estas estrofas riman en consonante, el

primero con el segundo y el tercero con el cuarto, y el quinto verso, rima en

asonante con el último verso de la estrofa inmediatamente anterior. El ritmo

del poema es trocaico, ya que el acento estrófico recae en sílaba impar y hay

un acento que se repite en la cuarta sílaba de cada verso.

Al

reparar en la estructura Interna del poema, vemos que lo podemos dividir,

claramente, en dos partes simétricas entre las cuales se establece un

paralelismo antitético. La primera parte está constituida por las dos primeras

estrofas (versos uno a once) y se centra en la caracterización de un tú

femenino. Lo primero que tendemos a pensar como lectores, es que el yo lírico

se está refiriendo a una mujer y, por la descripción que hace de ella, a una

mujer imposible, a un amor imposible. Independientemente de que esto pueda

llegar a ser así, creo que tendríamos que recordar lo que ya he referido en

artículos anteriores sobre la identificación que hace el poeta de las rimas, de

la mujer con la poesía. Para Bécquer la mujer es la encarnación de los

sentimientos, y la poesía es sentimiento, de manera que cuando dice “poesía eres

tú” en la conocidísima Rima XXI está

haciendo mucho más que un cumplido, está dando su visión poética. En este

sentido, ese tú femenino inaprensible al que se refiere en las dos primeras

estrofas podría llegar a ser, desde mi punto de vista, tanto una mujer amada,

como la poesía misma, como el hecho poético mismo. La segunda parte de la

estructura interna está constituida por las dos últimas estrofas (versos doce a

veintidós). Aquí el poeta caracteriza el “yo” como un

buscador incansable de ese ideal inalcanzable.

La

primera estrofa, que como indiqué tiene la misma estructura que la tercera, es

un gran hipérbaton, que hace que todas las características que se describen en

los cinco primeros versos, todas las imágenes que se acumulan converjan en el

verso final, en el “eso eres tú”. Aquí se caracteriza al “tú” y en la tercera

se hace lo propio con el “yo”. A su vez, toda la estrofa es una gran metáfora

impura, porque están presentes los dos términos, o sea está mencionado el

objeto que se metaforiza, encontramos en la estrofa una serie de metáforas que

convergen en el “ese eres tú”. Las imágenes son de una enorme variedad, tanto

en lo visual como en lo sonoro, pero, como es típico en Bécquer, todo es muy

vago, muy etéreo, carente de materialidad. El sonido del arpa es un “rumor

sonoro”, un sonido suave, apagado. Las imágenes que podrían sugerir algo de

materialidad, están atenuadas. Por ejemplo, el cendal se diluye, porque no es

un cendal real sino de bruma, no es un verdadero tejido, es un cendal

metafórico. Lo mismo sucede con la cinta, que es de blanca espuma. Los versos

quinto y sexto podrían dar la sensación de materialidad con el beso, pero es un

beso del aura. Aquí se ve claramente algo que expresé en el primer artículo que

publiqué sobre Bécquer, me refiero a ese estilo que hace pensar en la pintura

impresionista. Aquí todo parece inmaterial, incorpóreo, etéreo, fantasmal,

donde no hay contornos definidos. La combinación de versos de arte mayor y arte

menor, de un modo distinto a como lo hace en las estrofas pares le da a esta

estrofa, lo mismo que a la tercera, una variedad rítmica que le sirve para

caracterizar a ese “tú”, que como referí puede hacer referencia a una mujer, un

amor, pero también se puede referir a la poesía.

En la

segunda estrofa, aparte del cambio métrico ya señalado en la referencia a la

estructura externa, aparece un elemento novedoso que no estaba en la primera,

el yo. Aquí se muestra esa incesante lucha con la intención de alcanzar el

ideal. El intento del yo parece ser imposible, porque el verbo tocar, alude al

sentido del tacto y él intenta tocar algo inmaterial. La comparación, que

aparece con la reiteración del nexo “como”, tiende a resaltar la forma en cómo

ella se desvanece, (llama, sonido, niebla, gemido). Estos versos de estructura

paralelística, se encuentran divididos por una coma en dos hemistiquios. Hay

una correspondencia entre los hemistiquios, los dos primeros se refieren a lo

visual y los dos segundos a lo sonoro. El final de esta segunda estrofa remite

al final de la primera, refiriendo un color que, en los románticos, y después

en los simbolistas, va a ser tomado como el color ideal.

Lo

primero que notamos al entrar a la segunda parte del poema, a las estrofas que

se centrarán en caracterizar al “yo”, es una sonoridad muy fuerte que contrasta

con lo que se decía del tú. Las imágenes de diversos elementos naturales con

que se identifica al yo son más violentas. Son imágenes dinámicas, en

movimiento. Esa “ansia perpetua de algo mejor”, es una buena caracterización

del romántico en general, de la inconformidad romántica. Este yo es un ser

incompleto que carece totalmente de destino. Es una onda sonante en un mar sin

playas, no tiene límites, ni sitios donde aferrarse. Es un cometa errante, pero

en el vacío, no hay nada concreto, porque lo concreto sería la realidad y eso

no es para el romántico. Lo que es propio del romántico es el dolor

inconsolable, expresado aquí en ese “largo lamento del ronco viento”.

En el

primer verso de la última estrofa hay un elemento que parece dejar en claro que

el poeta se está refiriendo a una mujer, los ojos. Y seguramente sea así, a mí simplemente me pareció importante recordar la identificación que hace este

poeta, entre la poesía y la mujer amada. Si aceptamos que esta identificación

existe dentro de su poética, como de hecho existe, también es posible que el tú

que aquí se ha referenciado sea la poesía, el hecho poético como tal, que para

Bécquer es inalcanzable e inexpresable, como pudimos ver claramente en el

análisis literario de la Rima I. Ese

“volver los ojos noche y día”, está relacionado con el “ansia perpetua” de la

estrofa anterior. Hay un intento en esa mirada de intensa súplica, de encontrar

algo mejor, de encontrar ese tú que él aspira. En el tercer verso vemos que el

poeta interpuso el verbo “corro” entre los dos elementos coordinantes,

“incansable” y “demente”, pareciera como si hasta sintácticamente se expresara

esa demencia que sufre, porque es un verso cuyos elementos se encuentran

desordenados. Se cierra el poema haciendo referencia a que ese “tú” es una

visión. Ella es la “hija ardiente” de lo que lleva el romántico consigo en su

interior. Lo ardiente es el anhelo del yo.

Artículo publicado en la revista digital Vadenuevo www.vadenuevo.com.uy . Enero de 2018.

Suscribirse a:

Comentarios (Atom)